Ndiame Diop becomes Nigeria’s World Bank Country Director after Shuham Chaudri

Ndiame Diop resumed office yesterday as the new World Bank country director after Shubham Chaudri, the man that occupied the office since 2019 left last month. This is the second time in under a year that the Bretton Woods institution are changing their leadership in Nigeria. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) replaced Ari Aisen as its country representative in October 2023 with Christian Ebeke. It is also the first time that the two positions are occupied by Africans. Ndiame Diop, the new country director for the World Bank is a Senegalese national while Christian Ebeke is a Cameroonian. Shubham Chaudri before he left was perhaps the most visible World Bank country director, at least since the Victoria Kwakwa. Under his leadership, the World Bank portfolio in Nigeria expanded significantly, with about 30 projects and programmes approved under his leadership. Some of the programmes / projects include the recent combined US $2.25 billion for reforms for economic stabilization to enable transformation (RESET) development policy financing programme (DPF) for US $1.5 billion, and the US $750 million for the Nigeria accelerating resource mobilization reforms (ARMOR) programme for results (PforR). Indeed, under Chaudri leadership in Nigeria, the World Bank approved an estimated US $19 billion for about 30 projects in the country between 2019 and 2024. Nonetheless, Nigerians will not easily forget the US $1.5 billion that was not approved for the Nigerian government as budget support in 2020, following the Bank’s policy credibility concerns. At the time, sources close to the Bank said, ““There is skepticism about the commitment to structural reform. They are trying to ensure the reforms started are followed through and the commitment is credible. Therefore, unless the i’s are dotted and the t’s are crossed, the fund will not be released.” At the time, the focus of the credibility concerns by the Bank were the multiple exchange rates, and fuel subsidy. The reason the government was able to access the funds four years after is because it has now adopted a single exchange rate market and removed fuel subsidies June 2023. Diop arrives in Nigeria with similar credentials to Chaudri. According to the statement released by the Bank, he “served as the World Bank country director for Brunei, Malaysia, Philippines, and Thailand, based in Manila. In this position, he more tripled the Bank’s financing to the Philippines to scale up the Bank’s support to key economic reforms (policy based budget support programme) and the nation’s endeavour to bridge disparities in various sectors, including nutrition, stunting, healthcare, social protection delivery, education, agriculture, and digital connection.

Interest rate decisions cannot be arbitrary … Let’s focus on stability first

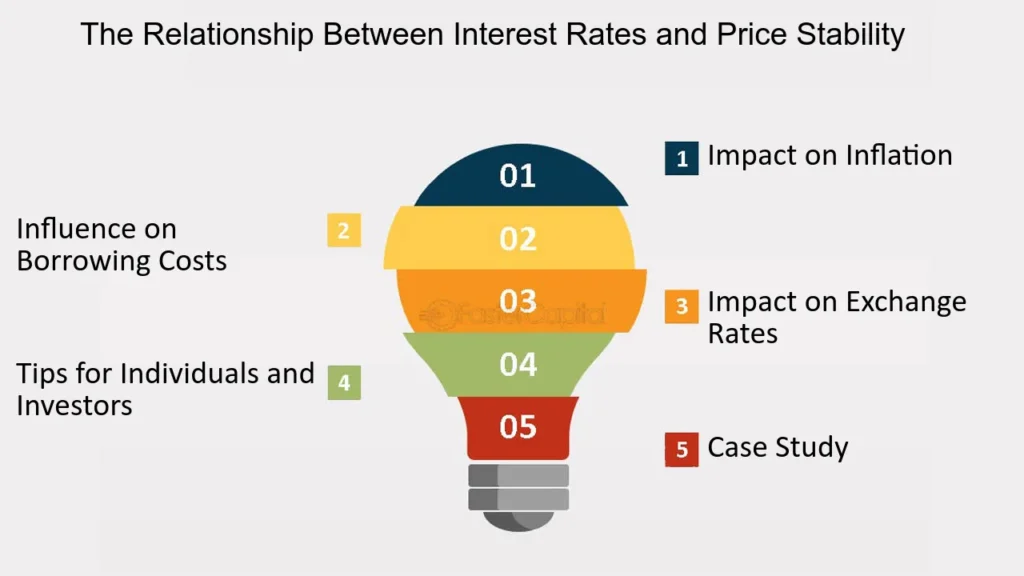

Later this month, the monetary policy committee (MPC) of the Central Bank of Nigeria (CBN) will meet to determine interest rates – unchanged, raise, or reduce. The committee at the 295th meeting of the MPC held on 20th and 21st of May 2024 raised the monetary policy rate by 150 basis points to 26.25% from 24.75%. See fig. 1. Fig. 1. The Dynamics of the Monetary Policy Rates of the Central Bank of Nigeria 2014 – 2024. Following recent ferocious argument about lowering interest rates, the 296th meeting on the 22nd and 23rd of July now has greater significance. Yes, the recent argument that the CBN should lower its interest rates is not new. The argument is as old in Nigeria and elsewhere as the notion of interest rate itself. It is an enduring argument that will continue to be made. In Nigeria, the main proponents have always been the Nigerian Association of Chambers and Commerce, Industry, Mines, and Agriculture (NACCIMA), the Lagos Chambers of Commerce and Industry (LCCI), and the Manufacturers Association of Nigeria (MAN), all for obvious reasons. However, the latest argument was forcefully made by Aliko Dangote, an industrialist and Africa’s richest man. He said at the opening session of a three-day national manufacturing policy summit organized by MAN in Abuja, “nobody can create jobs with an interest rate of 30%. No growth will happen. No power, no prosperity. No affordable financing, no growth, no development. What these arguments stresses is that monetary policy does not work in Nigeria like it does in other countries. Essentially, that the increases in interest rates do not lead to a reduction in consumption and investments. According to these arguments, price increases are caused by supply constraints because of large informal markets, and lower interest rates is required to deal with unemployment and poverty in the country. I understand these sentiments, but while monetary policy does not work perfectly, it does work. Before the MPC can start to lower interest rates, I expect that it will look out for when current trajectory of inflation peaks. The current trajectory started in May 2022 on the back of the Russian / Ukraine war that started in February 2022. Before that could peak, the removal of fuel subsidy and exchange rate reforms of June 2023 led to another spike from July 2023. Between May 2022 and May 2023, inflation increased from 17.7% to 22.4%, and between June 2023 and May 2024, inflation increased from 22.8% to 33.95%. Contrary to what many people may think, all central banks, including CBN prefers a trajectory of low interest rates, but the conditions and macroeconomic environment must be right for doing so. Any arbitrary, forceful, or pressurized lowering of interest rates will only jeopardise the growth and jobs we seek. Any arbitrary reduction in interest rates that fails to take into consideration prevailing macroeconomic conditions will only lead to further instability, jeopardise future growth and jobs. Fig. 2. The Policy Rates for Nigeria, South Africa, Ghana, Kenya, US, and the UK 2014 – 2024. As fig. 2 shows, the global economy started to see increases in interest rate in early 2022, all responding to different levels of inflation in their economies. In these other economies, just as in Nigeria, the risk of inflation remains elevated. Indeed, I shared most recently in the 2024 board retreat of Vitafoam Plc, all macroeconomic risks are currently elevated. Exchange rate, growth, income, and interest rates risks are all elevated. In such prevailing circumstances, there is not a magic wand, and the arbitrary reduction of interest rates will certainly make the situation worse. The elevated risks for interest rates come from rising inflation, rising government debts and deficits, and the weak Naira. Between April 2023 and April 2024, money supply increased by 173%, energy prices by 122%, exchange rate by 81.32%. These are not circumstances that dictate a reduction in interest rates. Interest rate decisions are considered based on macroeconomic conditions and environment. This includes balancing consumption, savings, and investments. That is often fairly understood. What is often not obvious is that all global economies compete for the pool of capital available. So, in addition to using the changes in interest rates to check inflation, central bankers are also mindful of capital flight. For instance, fig. 2 and 3 show the dynamics of the policy rates and inflation in six countries, including Nigeria. The other countries are Ghana, Kenya, South Africa, UK, and US. For four of those countries – Kenya, South Africa, UK, and US, the rate of inflation is less than 10%. Only Nigeria and Ghana have inflation currently above 20%. Ghana has inflation at 23% while Nigeria’s inflation is at 33%. But what is even more important is that the recent inflation trajectory has peaked in all the countries except for Nigeria. Despite that, interest rates trajectory has not started to come down because the central bankers are careful not to reduce interest rates too early. Fig. 3. Inflation dynamics for Nigeria, South Africa, Ghana, Kenya, US, and UK 2020 – 2024 Also, for all the countries considered, Nigeria has the highest gap of negative real interest rates – that is the gap between interest rates, which is the reward for savings, and inflation, which is the costs of savings. Any arbitrary reduction in interest rates will expand the gap between the reward and costs of savings, declining savings further, and worsen Nigeria’s capital flight. Indeed, Nigeria is the only country currently with a negative real interest rate. And as the graph in fig. 4 shows, it is the rate raises by the CBN in the last three meetings that have closed that gap. There is no greater evidence than this that the CBN is not as hawkish as some would like us to believe. Fig. 4. Nigeria’s inflation and the dynamics of the CBN’s monetary policy rate 2020 – 2024. Finally, the same argument that higher interest rates do not generate growth and jobs works in the other