Following the circular by the Central Bank of Nigeria that reintroduced fees to cash withdrawals at the ATMs, the Banks started implementation March 1st 2025. Under the new fee structure, customers will no longer receive three free interbank ATM withdrawals per month. Instead, withdrawals at on-site ATMs will attract a ₦100 fee per ₦20,000, while off-site ATMs may include an additional surcharge of up to ₦500 per transaction. The policy also standardizes POS cash withdrawal fees, bringing both services under the same pricing model.

Under the new structure, withdrawals from a customer’s own bank’s ATMs (On-Us transactions) remain free of charge. However, using another bank’s ATM (Not-On-Us transactions) will incur a ₦100 fee per ₦20,000 withdrawal. For off-site ATMs—those located outside bank premises, such as in shopping malls or fuel stations—an additional surcharge of up to ₦500 may apply. This surcharge will be displayed on the ATM screen before the transaction is approved, allowing customers to make informed decisions.

Banks must now clearly disclose all transaction fees, and customers can report overcharges to the CBN or their banks. Transfers and digital payments remain unaffected by the new policy, which solely applies to cash withdrawals

The reason for the reintroduction of the charges is simple – bank customers rarely have access to cash at ATMs anymore. The point was forcefully made to the Governor of the Central Bank of Nigeria Yemi Cardoso during the annual bankers’ dinner late last year and the governor promised to do something about it. It was also clear that free ATM withdrawal was not sustainable.

In the last five years, the growth in the deployment of ATM machines have stalled. In the same period, the number of POS merchants, originally designed for direct card purchase from merchants and a back stop to improving financial inclusion in the rural areas with very limited access to ATMs have risen.

This change stems from the rising cost of maintaining ATMs and digital banking infrastructure. Previously, Nigerian bank customers could withdraw cash from interbank ATMs for free three times a month, after which a ₦35 fee applied per transaction. POS transactions, however, were largely unregulated, with agents setting their own fees—often charging ₦300 or more per ₦10,000 withdrawal. While ATMs provided a lower-cost alternative, their scarcity and frequent downtimes meant many Nigerians relied on POS agents, despite higher charges.

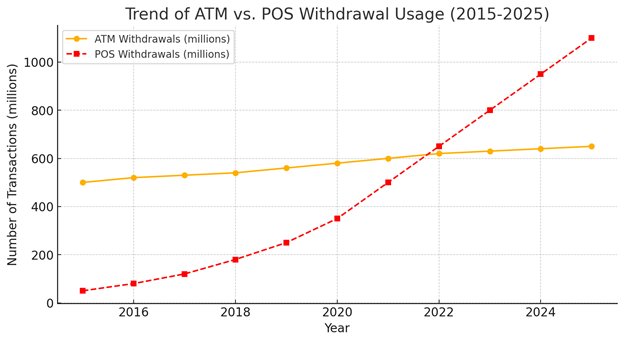

Fig. 1. ATM versus POS withdrawal 2015 – 2025

Graph showing the trend of ATM vs. POS withdrawal usage from 2015 to 2025. ATM withdrawals have grown gradually, while POS transactions have surged, especially in the last few years.

Two things aligned to spike the use of POS for cash in urban areas. As mentioned above and shown by the graph, Banks could not sustain the maintenance of the ATMs machines, especially as it was free to customers. The rising costs coincided with the rapid decline in Naira’s exchange rate against all international currencies. The costs of maintenance are largely in foreign currencies. Secondly, banks realised they could not only shirk their responsibility, but their staff also make quick money through POS merchants.

The expectation is that the new measures will encourage banks to expand ATM deployment. However, as the graph below shows, following the growth in ATM deployment between 2010 and 2021, ATM deployment has stalled. The brief data below shows that Nigeria has one ATM to 10 ATMs 100,000 people. It was 16.5 to 100,000 in 2021 according to data from Trading Economics. In South Africa, it is 50 to 100000 between 2005 and 2022.

According to Liberman Companies, the costs of an ATM ranges from US $2500 to US $8000 depending on the display type, cassette size, and security features. To raise the current level of ATM to pre pandemic levels will require investments of up to US $10 m to US $32 million [ N15 billion – N48 billion]. This analysis points to the conclusion that the price for cash withdrawals does not provide sufficient incentives for this renewed investment by banks.

The difference between withdrawal from own’s bank (free) and withdrawing from another bank’s ATM (N100) is not sufficient to prevent a free loader mentality – where each bank expects the other to provide services to its customers because the N100 is largely insignificant.

Fig. 2. The fall of ATM deployment in Nigeria from 2021.

Graph shows ATM deployment data in Nigeria from 2010 to 2022. It reflects the steady growth of ATMs until 2021, followed by a decline in 2022.

A corollary of this measure should be to minimise the use of cash in the first place. The use of POS for cash, rather than for merchandise is the problem. POS is meant for merchandise but has become the intermediary.

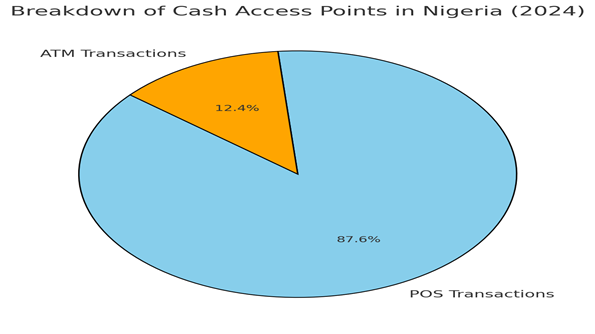

Fig. 3. ATM and POS transactions in 2024.

Pie chart showing the breakdown of cash access points in Nigeria for 2024. POS transactions dominate with 87.5% of the total, while ATM transactions account for only 12.5%.

It is obvious that POS machines are not serving as complementary to ATMs as it was intended. They started to serve as competition. So, as competitors and or complementary, the system failed when it became clear that it became the only option (monopoly) in the access to cash game. There is nothing to now suggest that the fees attached to only non-own bank withdrawal is sufficient to change that.

The debate over treating ATMs and POS terminals under the same fee structure is gaining traction. Even if there are improvements in the urban areas because that can easily be monitored, it is likely that POS agents will remain the primary cash withdrawal source due to the limited availability of ATMs in the rural areas.

Nigeria’s cash availability structure has evolved significantly. In the early 2000s, transactions were largely confined to bank branches, with long queues and slow processing times. The introduction of ATMs improved access but remained limited due to poor infrastructure and a low number of machines per capita. The CBN attempted to ease these issues by mandating interbank ATM withdrawals and later allowing three free transactions per month, yet cash access continued to be unreliable, particularly in rural areas.

The rise of POS agents in the 2010s provided an alternative solution, allowing people to withdraw cash from local vendors. However, the present crisis is rooted in the 2022 / 2023 Naira redesign crisis, when physical cash became scarce, POS agents exploited the situation, charging withdrawal fees as high as ₦2,000 per ₦10,000. This period exposed weaknesses in Nigeria’s cash distribution system, revealing an overreliance on POS networks rather than structured ATM expansion.

Now, the latest CBN policy standardizes ATM and POS fees to create a more predictable cash withdrawal system. While this could help regulate POS charges and prevent extreme variations, it also raises concerns that customers will face higher withdrawal costs with no immediate benefit. Banks may delay expanding ATM deployment, leaving many Nigerians with fewer options and higher financial burdens. Additionally, the reality is that POS vendors will likely take their pricing cues from banks and continue to adjust their fees accordingly. This means that instead of reducing withdrawal costs, customers may see even higher charges as POS agents pass on their operational costs. With bank ATM networks still limited in certain areas, the true impact of this policy on cash availability and affordability remains uncertain and whether this policy leads to a more efficient cash withdrawal system or if it simply increases withdrawal costs without tangible improvements remains to be seen.